- Home

- POSTER GALLERY

- ❗️BOOK & POSTER STORE❗️

- PURCHASE "HJ Quex" film ephemera HQ

- About the Posters

- The William Gillespie Collection

- Our Publishing House

- ❗️GFDN interviews author and collector William Gillespie ❗️

- Our most expensive & inexpensive finds!

- ❗️***NEW!**❗️POSTER OF THE MONTH - Blutzeugen / Raza

- ❗️NEW ❗️Film Posters – Demands on an important means of film advertising. ❗️

- In our Book + Zeitschrift Library

- ❗️ ***NEW!*** Hitler Youth Quex – A Guide for the English–speaking Reader ***NEW!*** ❗️

- ❗️***NEW!*** Table of Contents of our new HJ QUEX book❗️

- ❗️Hitler Youth Quex Guide - early praise! ❗️

- Recent loans from the Collection

- Farewell Horst Claus. (1940–2024 †)

- "Der Deutsche Film" Zeitschrift

- ❗️ ***NEW!***Reichsfilmkammer collection ❗️

- German "Tendency" Films (Tendenzfilme) in the Third Reich

- KARL RITTER

- Karl Ritter original film posers in this Collection

- "Besatzung Dora" ( † 1943)

- "The Making of The Crew of the Dora"

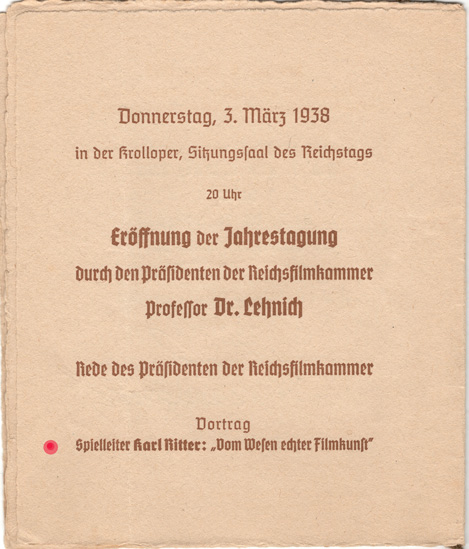

- Karl Ritter at the 1938 Reichsfilmkammer Congress

- INDEX -"Karl Ritter" book, 2nd edition

- Karl Ritter's Legion Condor (1939, unfinished)

- Excerpt from our "Dora" book

- ∆∆∆∆∆ High praise for our DORA book! ∆∆∆∆∆

- TABLE OF CONTENTS – "Legion Condor"

- § § § § § Early Praise for our LEGION CONDOR book! § § § § §

- ❗️"Das Leben geht weiter" and Karl Ritter ❗️

- Dateline: Ufa - April 11, 1945

- Zarah Leander Europe–wide !

- Japan Military Film and Karl Ritter

- Karl Ritter after 1945

- 1935 Film Congress

- Poster Exhibition in Berlin, March 1939

- Potsdam poster exhibition 12 April–25 August 2019

- Leni Riefenstahl's two "Olympia" Films (1938)

- "Ohm Krüger" (1941)

- Emil Jannings

- "Blutendes Deutschland" (1933)

- Hannes Stelzer ( † 1944)

- Klaus Detlef Sierck ( † 1944)

- Film stills

- Reich Film Censorship Offices

- ❗️***NEW!***The Fate of the German Film Industry in May 1945 ❗️

- Film censorship cards

- Film Archives

- Cinema advertising

- School filmstrips

- ❗️UPDATED❗️ Z F O / Ostland Film G-m-b-H

- Z F O / Herbert Jacobi estate

- ZFO / Ostland Film newspaper articles

- ❗️***NEW!*** Roter Nebel / Red Fog / Red Mist (1942/1943, ZFO) ❗️

- ZFO - Der Rückkehrer - The Returnee (1943/1944)

- The D F G production company

- D I F U

- ❗️ ***NEW!*** "Carl Peters" – Special Collection. ❗️

- "Alcazar" (1940, Genina)

- "Der 5. Juni" (1943, banned)

- Herbert Selpin and his "Titanic" (1943)

- Ein Robinson (1940, Fanck)

- "Fronttheater" (1942)

- Veit Harlan's Jud Süß and Fritz Hippler's Der Ewige Jude

- Harlan "Jud Süß" trial 1949

- Werner Krauss & JUD SÜß

- Anti-Semitic Film Posters in the Collection

- "Heimkehr" (1941)

- "Hitlerjunge Quex" (1933)

- ❗️***NEW!*** Hitlerjunge Quex in 111 Greater Berlin Cinemas ❗️

- Jürgen Ohlsen

- "S.A.Mann Brand" (1933)

- "In der roten Hölle" (Edgar Neville, 1939)

- "Helden in Spanien" (1938)

- The Spanish Civil War in Film

- Andrews Engelmann (1901 – 1992)

- Deutsche Wochenschau

- Uƒa Feldpost

- Uƒa Kulturfilm – Informationen

- " Die Tochter des Samurai" (1937, Fanck)

- Ufa 25th Anniversary

- Invitations to world premieres

- ❗️***NEW!*** Continental Films, Paris 1940–1944 ❗️

- Film Censorship in Occupied Paris 1942

- "Der Sieg des Glaubens" (1933)

- Wilhelm Althaus Estate

- Weimar Germany posters

- Ufa and the Ordensburgen

- The Gaufilmstelle in our Collection

- "Zwei Welten" (1940)

- "Capriccio" (1938) –Karl Ritter film album

- Unrealised NS Propaganda Films 1934–1945

- German Film Directors accused of "war crimes"

- Australian––themed NS feature films

- "Der Störenfried" / "The Troublemaker"

- What was new in 2014?

- What was new in 2015?

- What was new in 2016?

- What was new in 2017?

- What was new in 2018?

- What was new in 2019?

- What was new in 2020?

- What was new in 2021?

- What was new in 2022?

- What was new in 2023 ?

- What's new in 2024?

- ❗️***NEW!*** Hitler assassination attempt in Karl Ritter film cut❗️

- BESATZUNG DORA private photos

- Just discovered 1942 article on BESATZUNG DORA

- The Karl Ritter Tetralogy

- Google Analytics 2023

- Our first–ever acquisition!

- ❤️"Some of our favourite things....!"❤️

- ERRATUM for our " Hitler Youth Quex Guide"

- Trending

- Vale †

- Our Wants List / 2024 / Wunschliste

- Pop Quiz

- Unsere KARL RITTER Bücher in Deutschland liefbar!

- WHERE to buy our books right now?

- ✉️Contact

“History is not about the facts. It is about the context and who is telling the story.” —Prof. Milton Fine.

“History is not about the facts. It is about the context and who is telling the story.” —Prof. Milton Fine.

"Who controls the past controls the future: who controls the present controls the past." –– George Orwell in his novel "1984."

"Whoever doubts the exclusive guilt of Germany for the Second World War destroys the foundation of post–war politics." –– Prof. Theodor Eschenberg, Rector, the University of Tübingen.

"If we have our own why in life, we shall get along with almost any how." – Friedrich Nietzsche

POSTER GALLERY --view

over 500 German film

original posters between

1927–1954 from

Germany and from

many Axis and Neutral countries

across Europe!

Note! Posters in the Poster Gallery are PERMANENT

acquisitions which are NOT FOR SALE!! ONLY the

posters listed in our POSTER STORE are for sale.

(They have a price and order button to use.)